History

HISTORY

It has been said that something in the water has given residents of the Shoals a special musical vitality. Archaeological evidence suggests that music played an important role in the lives of Native American peoples who inhabited the Shoals before the arrival of the first European settlers. The late Tom Hendrix, a local historian of Creek heritage, noted that flutes or whistles made of waterfowl wing bones and cane have been discovered in the area. Local legend holds that the Chickasaw people, who referred to the Tennessee as a “singing river,” believed that spirits in the water that sang to them, in voices ranging from soft to loud depending on the intensity of the currents. Centuries later, the sounds of nature continued to inspire Shoals residents like W.C. Handy, who was captivated by the calls of birds and other animals he heard while growing up near the banks of the Tennessee.

Many of the white settlers who moved into the region in the late 18th and early 19th centuries were of Scots-Irish descent. These settlers brought their Celtic traditions with them and made the fiddle a centerpiece of entertainment at dances and in contests. Meanwhile, African slaves who worked the cotton fields of area plantations had their own musical traditions, including chants, field hollers and songs of spiritual hope. By the dawn of the 20th century, these traditions had blended with the hymns and gospel music heard in area churches to create new musical styles that still paid tribute to their origins.

Handy, who was born in 1873 and raised in the Greater St. Paul AME church where his father served as pastor, recalled in his autobiography:

"It was my good fortune as a youngster to be the water boy in rock quarries, iron furnaces, on farms and on the Tennessee River… where I heard Negro laborers and steamboat roustabouts sing many work song, which since those days have been a part of musical America. It was such snatches of song that turned my attention to what we now know as the blues."

Florence native and Sun Records founder Sam Phillips echoed Handy in his appreciation of the Shoals as a musical “melting pot”:

"When I was growing up, we heard it all… In the fields we heard the black man’s blues, in the churches we heard black spirituals and white gospel, and on the radio we heard the Grand Ole Opry… Out of that we created a sound that’s hard to define, hard to pigeonhole, because it includes the best elements of all those tremendous sources."

Phillips also experienced harsh poverty during his childhood in the Shoals. The Great Depression and the death of his father in 1941 forced him to drop out of Coffee High School and work to support his mother and siblings. Florence-born music publisher and producer Buddy Killen likewise spoke of "relentless poverty" being "a constant part of [his] life" while he was growing up in the Shoals.

For Phillips, Killen and others of their generation, music promised "escape from their small-town existence." Killen "realized that he wasn't interested in working for Reynolds Aluminum or moving north for a factory job, so he left the Shoals for Nashville. The Shoals-based Blue Seal Pals (above) moved there, too, following a successful audition for Grand Ole Opry founder George Hay. Phillips, meanwhile, relocated to Memphis where he founded Sun Records and discovered Elvis Presley.

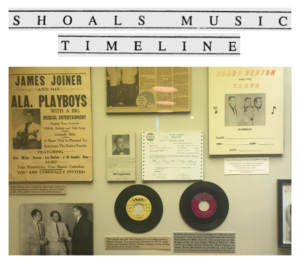

The resulting interstate "musical network" enabled bus-station owner James Joiner to launch Florence-based Tune Records, the first record company in Alabama. Tune, in turn, attracted musicians from more rural parts of north Alabama to the Shoals. Among them was bass player and aspiring songwriter Rick Hall, whose Tune-published co-write "Sweet and Innocent" was recorded by Roy Orbison in 1958. Three years later, Hall launched his own FAME Studios, which would establish Muscle Shoals as a "Hit Recording Capital" in its own right.

Explore the history of the Shoals recording industry with our new timeline feature by clicking below.

It has been said that something in the water has given residents of the Shoals a special musical vitality. Archaeological evidence suggests that music played an important role in the lives of Native American peoples who inhabited the Shoals before the arrival of the first European settlers. The late Tom Hendrix, a local historian of Creek heritage, noted that flutes or whistles made of waterfowl wing bones and cane have been discovered in the area. Local legend holds that the Chickasaw people, who referred to the Tennessee as a “singing river,” believed that spirits in the water that sang to them, in voices ranging from soft to loud depending on the intensity of the currents. Centuries later, the sounds of nature continued to inspire Shoals residents like W.C. Handy, who was captivated by the calls of birds and other animals he heard while growing up near the banks of the Tennessee.

Many of the white settlers who moved into the region in the late 18th and early 19th centuries were of Scots-Irish descent. These settlers brought their Celtic traditions with them and made the fiddle a centerpiece of entertainment at dances and in contests. Meanwhile, African slaves who worked the cotton fields of area plantations had their own musical traditions, including chants, field hollers and songs of spiritual hope. By the dawn of the 20th century, these traditions had blended with the hymns and gospel music heard in area churches to create new musical styles that still paid tribute to their origins.

Many of the white settlers who moved into the region in the late 18th and early 19th centuries were of Scots-Irish descent. These settlers brought their Celtic traditions with them and made the fiddle a centerpiece of entertainment at dances and in contests. Meanwhile, African slaves who worked the cotton fields of area plantations had their own musical traditions, including chants, field hollers and songs of spiritual hope. By the dawn of the 20th century, these traditions had blended with the hymns and gospel music heard in area churches to create new musical styles that still paid tribute to their origins.

Handy, who was born in 1873 and raised in the Greater St. Paul AME church where his father served as pastor, recalled in his autobiography:

"It was my good fortune as a youngster to be the water boy in rock quarries, iron furnaces, on farms and on the Tennessee River… where I heard Negro laborers and steamboat roustabouts sing many work song, which since those days have been a part of musical America. It was such snatches of song that turned my attention to what we now know as the blues."

Florence native and Sun Records founder Sam Phillips echoed Handy in his appreciation of the Shoals as a musical “melting pot”:

"When I was growing up, we heard it all… In the fields we heard the black man’s blues, in the churches we heard black spirituals and white gospel, and on the radio we heard the Grand Ole Opry… Out of that we created a sound that’s hard to define, hard to pigeonhole, because it includes the best elements of all those tremendous sources."

Phillips also experienced harsh poverty during his childhood in the Shoals. The Great Depression and the death of his father in 1941 forced him to drop out of Coffee High School and work to support his mother and siblings. Florence-born music publisher and producer Buddy Killen likewise spoke of "relentless poverty" being "a constant part of [his] life" while he was growing up in the Shoals.

For Phillips, Killen and others of their generation, music promised "escape from their small-town existence." Killen "realized that he wasn't interested in working for Reynolds Aluminum or moving north for a factory job, so he left the Shoals for Nashville. The Shoals-based Blue Seal Pals (right) moved there, too, following a successful audition for Grand Ole Opry founder George Hay. Phillips, meanwhile, relocated to Memphis where he founded Sun Records and discovered Elvis Presley.

For Phillips, Killen and others of their generation, music promised "escape from their small-town existence." Killen "realized that he wasn't interested in working for Reynolds Aluminum or moving north for a factory job, so he left the Shoals for Nashville. The Shoals-based Blue Seal Pals (right) moved there, too, following a successful audition for Grand Ole Opry founder George Hay. Phillips, meanwhile, relocated to Memphis where he founded Sun Records and discovered Elvis Presley.

The resulting interstate "musical network" enabled bus-station owner James Joiner to launch Florence-based Tune Records, the first record company in Alabama. Tune, in turn, attracted musicians from more rural parts of north Alabama to the Shoals. Among them was bass player and aspiring songwriter Rick Hall, whose Tune-published co-write "Sweet and Innocent" was recorded by Roy Orbison in 1958. Three years later, Hall launched his own FAME Studios, which would establish Muscle Shoals as a "Hit Recording Capital" in its own right.

Explore the history of the Shoals recording industry with our new timeline feature by clicking below.